Late this week I had to privilege to attend a conference celebrating the work of the historians C.A. Macartney and László Péter. The conference was jointly hosted by Károli Gáspár Református Egyetem (KRE) in Budapest and the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) at University College London (UCL) and held in the beautiful Károlyi-Csekonics Palota Ball Room on the KRE Campus in central Budapest.

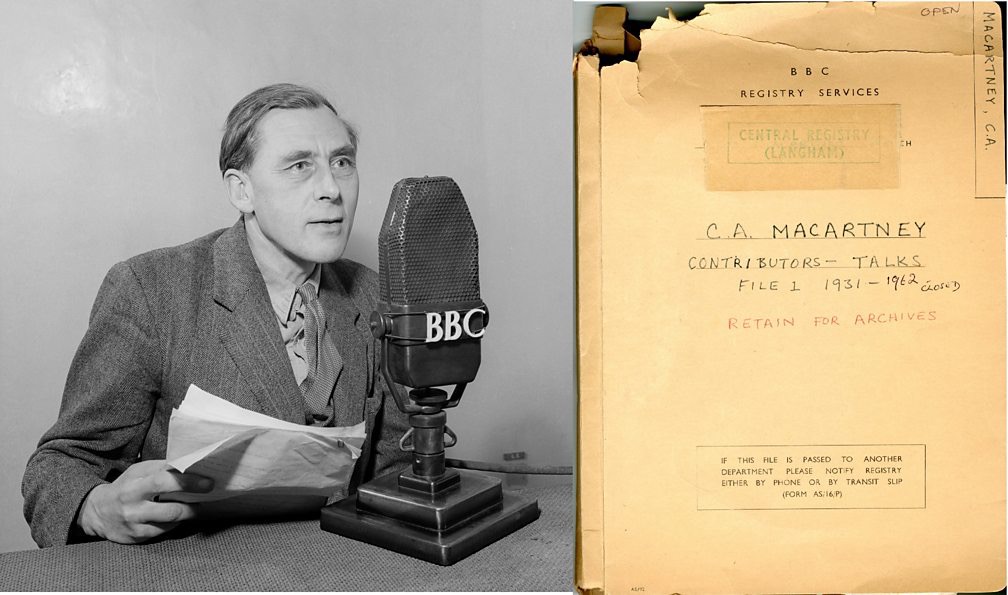

The attendees gathered to discuss the life and work of Macartney and Péter. Carlile Aylmer Macartney (1895-1978) remains one of the preeminent historians of Hungary and Central Europe in the English language. A product of the British public school system, Winchester College (1909-1914), his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge University were deferred by World War I in which he enlisted in the British Expeditionary Force. In late 1914 he was commissioned and served two years in the Hampshire Regiment before transferring to the Royal Field Artillery and served the duration of the war despite being wounded. Afterwards, he returned to his studies at Cambridge but did not complete a degree.

Instead, he traveled to Vienna where he worked as a journalist and then as a diplomat. His keen intellect and facility with language allowed him to engage the multicultural society of postwar Vienna where he met a variety of peoples including numerous Hungarian émigrés. After several years he left Vienna for the Royal Institute of International Affairs (commonly known as Chatham House) where he worked with the likes of Arnold Toynbee and R.W. Seton-Watson—whose work is often contrasted with Macartney’s. In 1936, he accepted a research position at All Souls’ College, Oxford University, where he balanced his academic work with policy work for the British Foreign Office; then in 1951 he also accepted a professorship at the University of Edinburgh along with his continued work at Oxford. Throughout his career, Macartney leveraged his significant linguistic abilities—including German, Classical Greek, Hungarian, and Latin—while blending his personal knowledge of Central European politics and culture with intensive studies of archival materials to produce hundreds of analytical works from policy documents to academic tomes. As a result, his positive view of Hungarians balanced by a critical, realist, political perspective earned him admiration in Hungary as a serious and impartial commentator; yet these views frequently diverged from that of others in British foreign circles, most notably Seton-Watson.

One of Macartney’s students was a Hungarian refugee named László Péter. Péter (1929-2008) was born in Hungary and completed his first degree at Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem (ELTE) and worked as an archivist and teacher afterwards. During the 1956 Revolution, he was a member of the revolutionary committee cataloguing the files of the Ministry of the Interior, including the documents of the secret police. As a result, he fled Hungary during the Soviet intervention and was resettled in the UK. He entered Oxford University where he met Macartney who would supervise Péter’s doctoral work. Soon afterward, he accepted a lecturer appointment at SSEES. There he researched and taught on Hungary and Central Europe, many of his students presented at the conference. Péter was described as being completely Hungarian while also the quintessential British academic.

A consistent theme of the conference was the relationship both Macartney and Péter had with Hungary. Both men worked at the intersection of academic and policy research related to Hungary; moreover, they did so from a position of critical fondness. Each carried deep affection for Hungary and the Hungarian people while also providing clear-eyed criticism of the structural and political shortcomings of the Hungarian state. Together they witnessed the political turbulences of their beloved Hungary including, a Bolshevik revolutionary government, a nationalistic regency, the Nazi-aligned Szálasi government, the postwar chaos, Rákosi’s Stalinist communism, an ill-fated revolt, Kádár’s “goulash communism,” and the transition to a liberal, pluralist, democracy. Throughout these changes Macartney and Péter remained steadfast proponents of Hungary while providing informed and insightful criticism of the illiberalism and abuses of the various regimes and governments. It is for this reason they both are respected as impartial scholars and friends of Hungary. Thus, the conference concluded with the unveiling of a large plaque honoring Macartney in the Castle District located near the former British Legation that he frequented.

This critical fondness is particularly important for any scholar regardless of time or location, yet it is especially relevant to those of us studying Hungary today. It is important to recognize a path between the extremes of obsequious patriotism and reflexive rejection. A model of accomplishing this is a legacy Macartney and Péter.

Postscript: In a seemingly apt coda, the day after the conference, thousands of loyal Hungarians gathered to voice their criticism of the state.