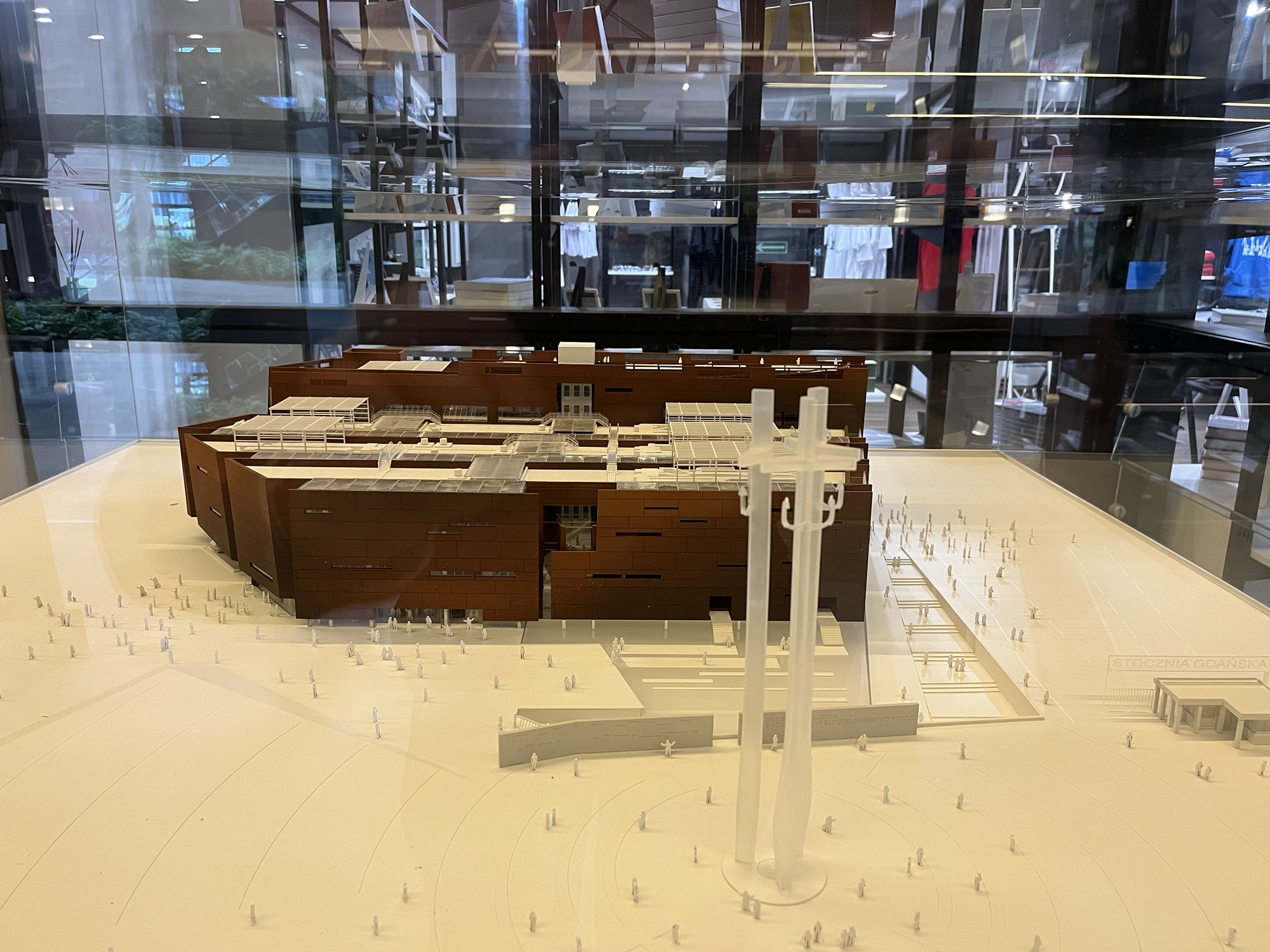

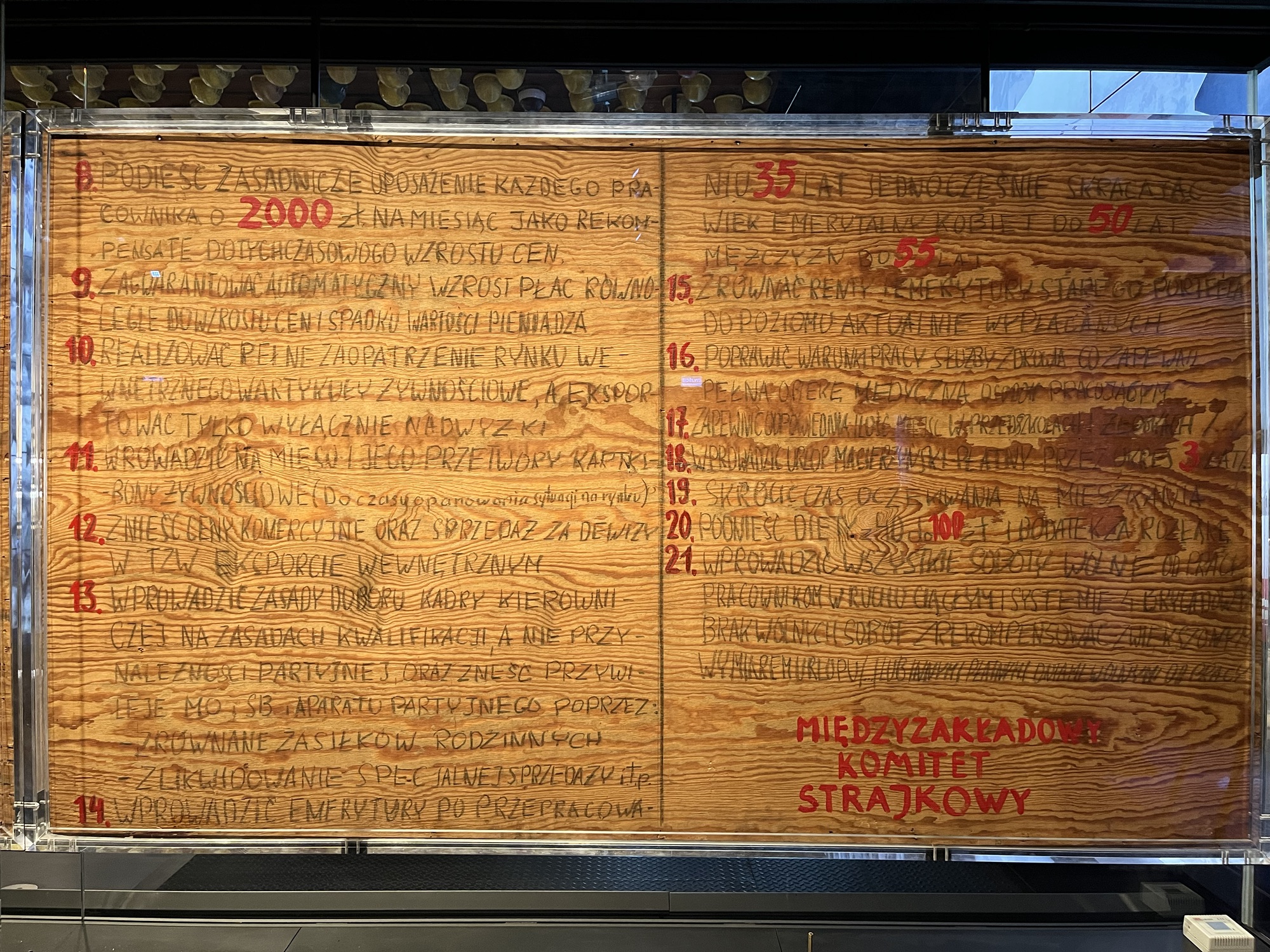

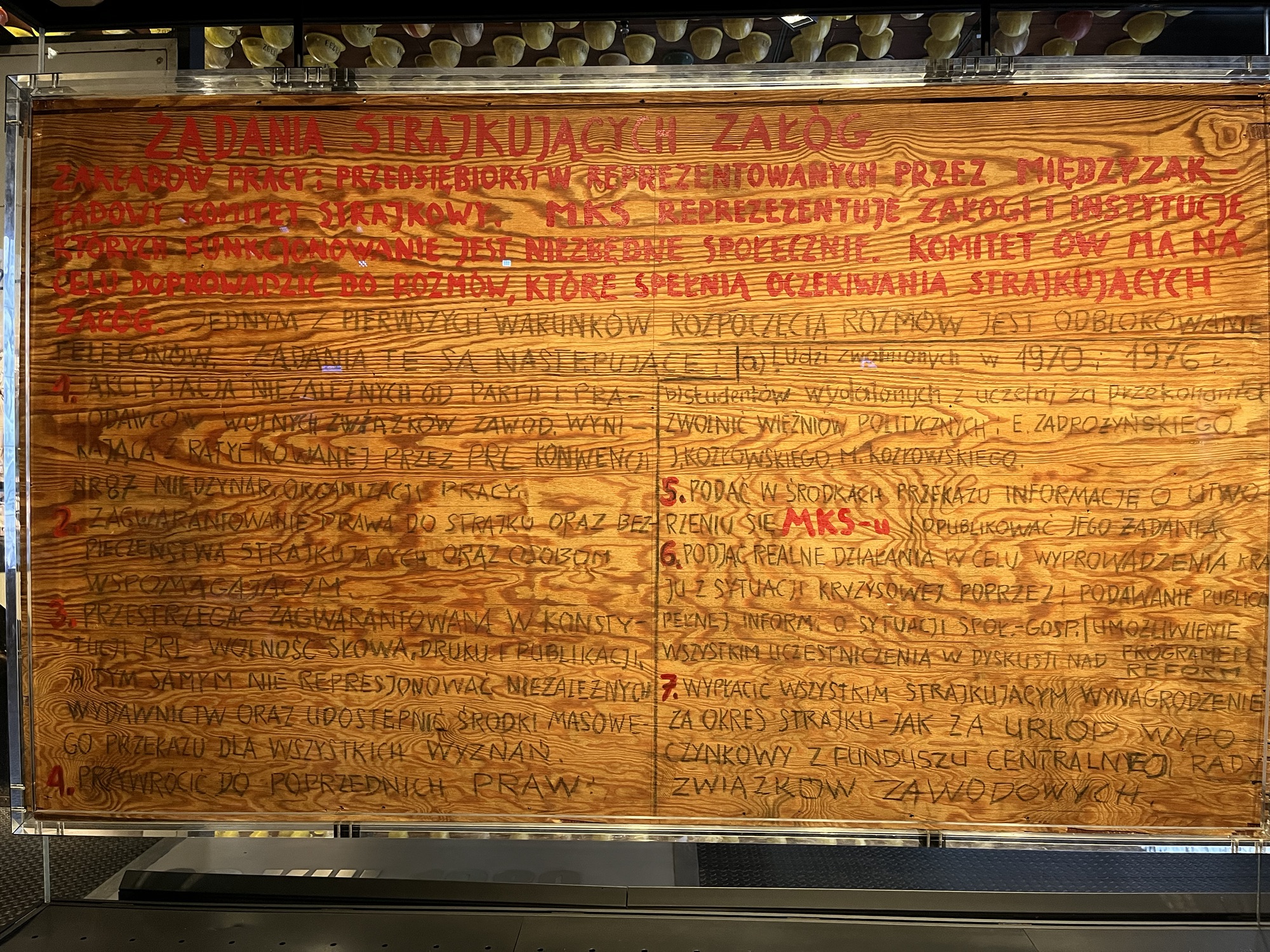

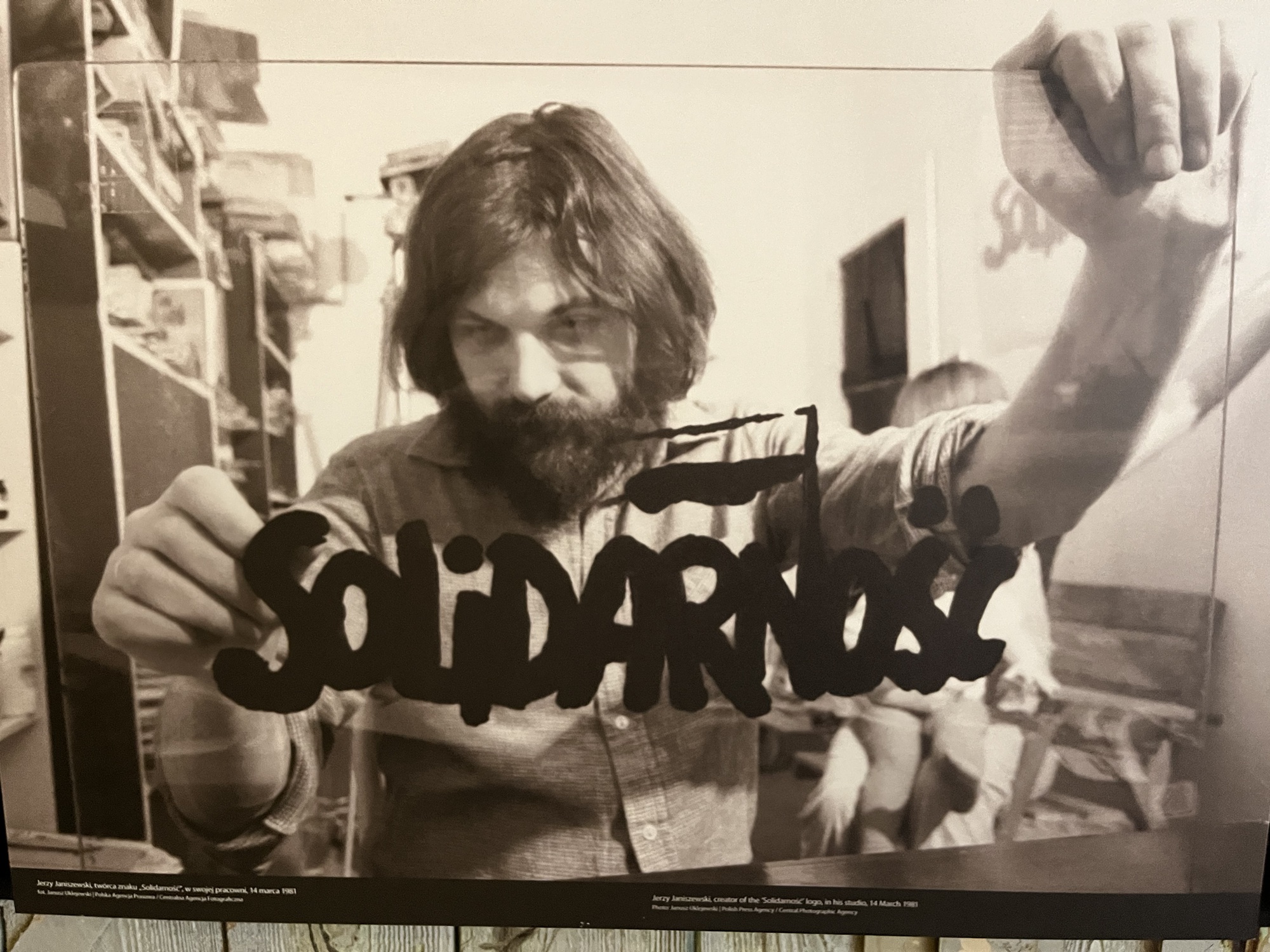

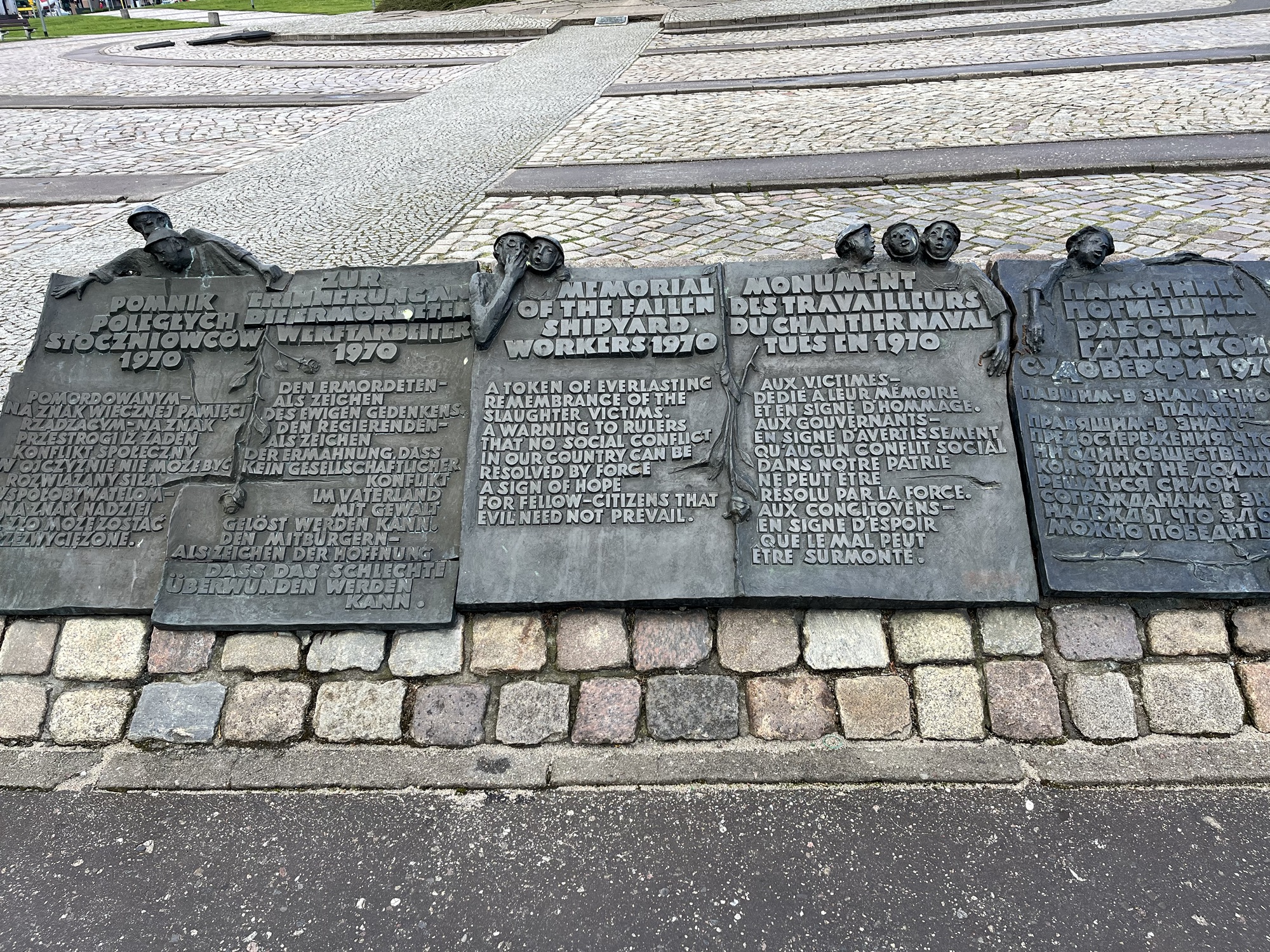

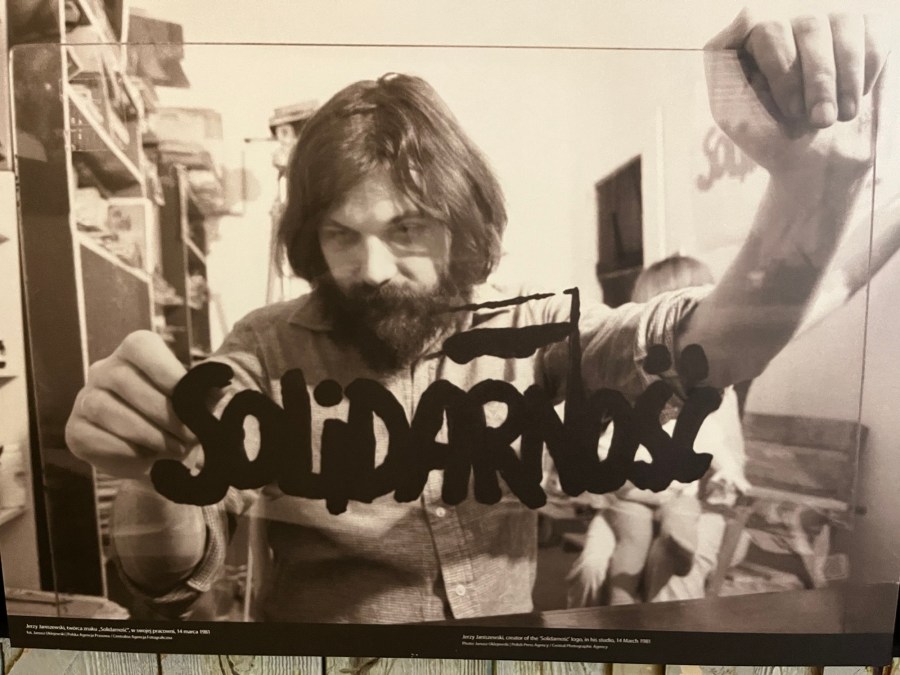

This past week I visited Gdańsk, Poland to guest lecture for the wonder Dr. Ania Marzurkiewicz and her graduate class on US-Polish relations. While in Gdańsk, my wife and I visited the European Solidarity Centre which houses archival collections related to Solidarność, the independent labor union that formed in Poland during the socialist era. The Centre also offers a fantastic permanent exhibit that tells the history of Solidarność from its beginning in August 1980, its unexpected success, its persecution and survival during General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s marital law, its resurrection in 1984, and its role in Poland’s transition from state socialism. The building, the exhibits, the audio guides, are world-class, if you are interested in the history of this period, the Solidarność movement, or in exhibit construction I cannot recommend this more strongly.

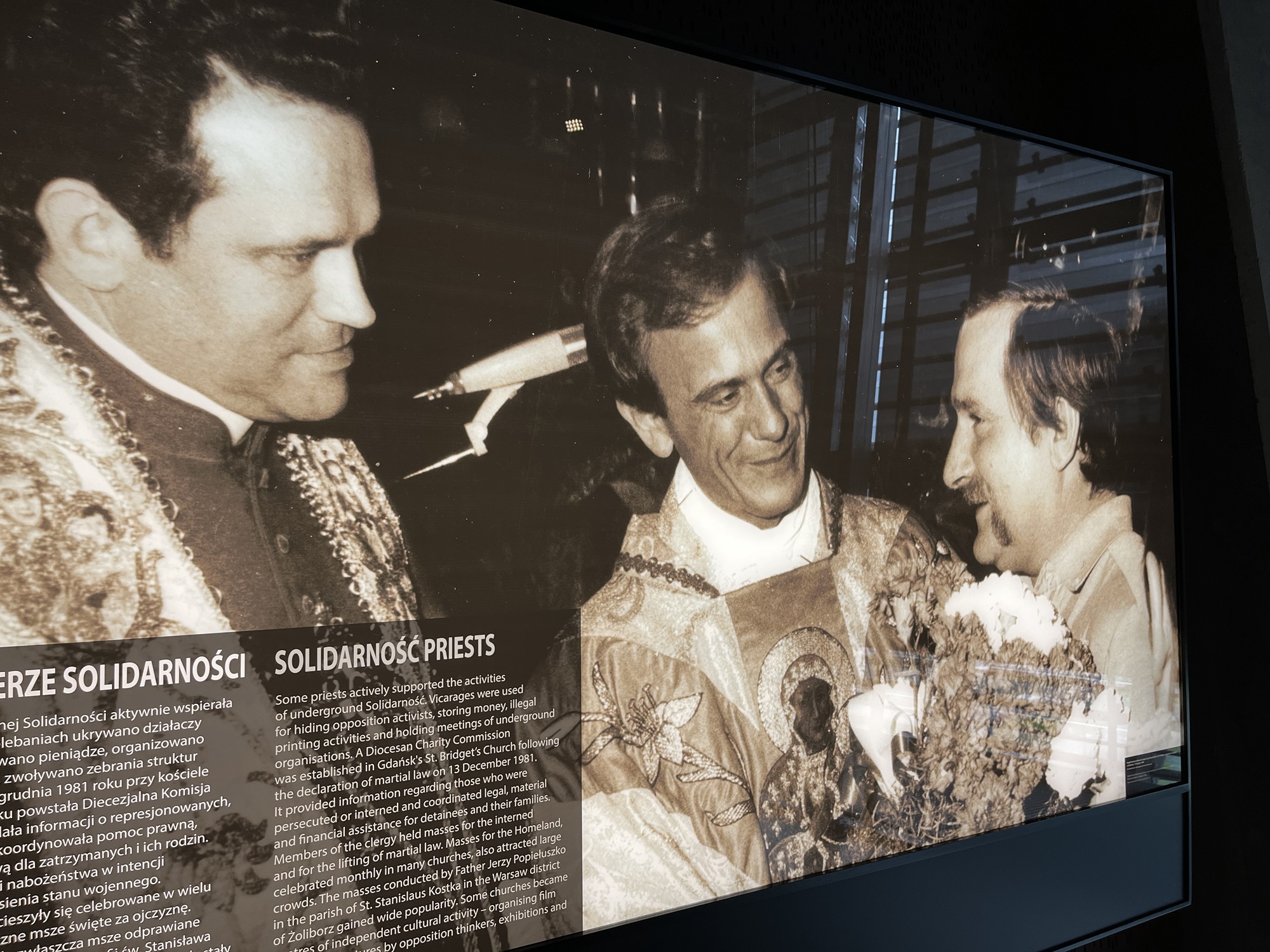

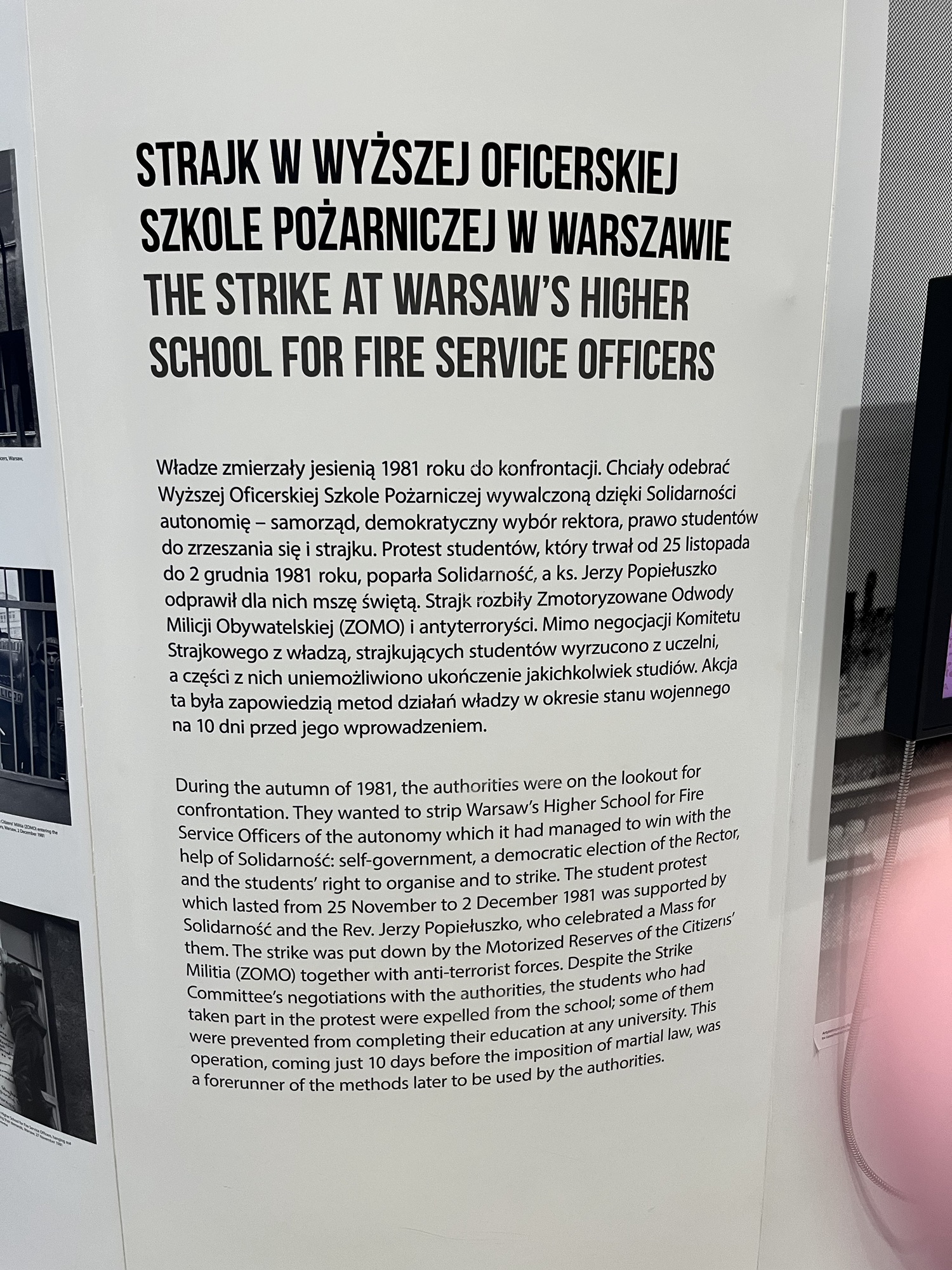

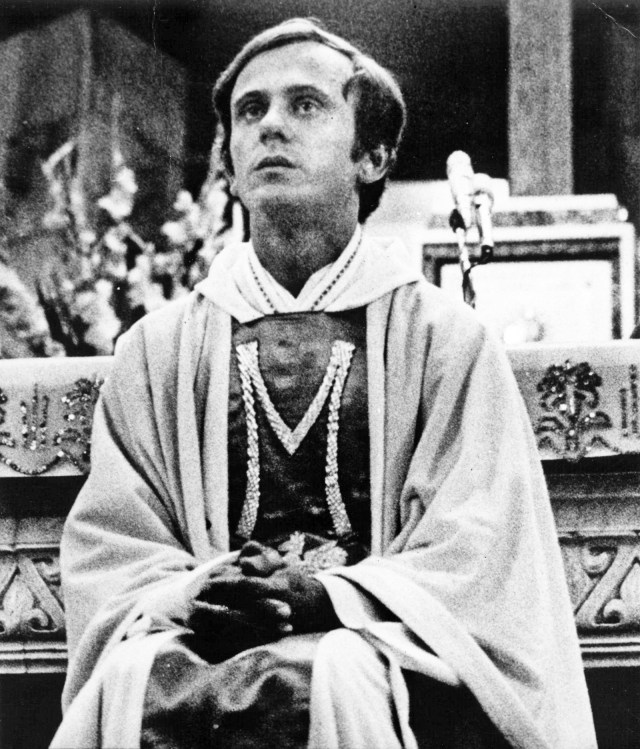

One of the aspects that particularly resonated with me was the role of the Solidarność Priests, including Father Henryk Jankowski and Father Jerzy Popiełuszko. These priests actively participated in the strikes and other activities of Solidarność. Several exhibits described the spiritual and moral support these priests provided to workers during strikes and to Solidarność members persecuted during the martial law.

Father Popiełuszko is particularly prominent in these exhibits, in part because in October 1984 officers of the Polish secret police assaulted him, bound him, and then threw him into the Vistula Water Reservoir. Because martial law ended in 1983, his murderers were arrested, tried, and convicted while thousands of mourners attended his funeral. The Roman Catholic Church beatified him as a martyr in 2010.

The inclusion of Father Popiełuszko in the Solidarność story is significant because often the role of spiritual life is omitted from historical events. While it is possible to tell the story of Solidarność without leaders like Popiełuszko, doing so flattens the narrative; Solidarność was not simply a labor movement, it was a national, cultural movement and the Catholic church played a significant role not only in the movement but in Polish society even during the socialist era.

Seeing the work of Father Popiełuszko resonated with me for another reason. One of the hidden gems of the Baylor University Libraries is the Keston Center for Religion, Politics, and Society that houses the records of the Keston Institute which documented religious life in communist countries. In the Polish subject files, there are numerous documents related to Father Popiełuszko because even before Solidarność he resisted the state’s efforts to curb religious life. The Keston Institute even produced a TV program about his life, “From Calvary to Komi: Father Jerzy Popieluszko,” which is part of the Keston Center’s Digital Collection. There are dozens of photographs and hundreds of documents in the digital collection and even more that are not digitized.

The life of Father Popiełuszko reminds us that religion, and Christianity in particular, remained an important facet of everyday life in socialist countries and that story remains largely untold. That is part of why I am a proponent for the Keston Center and why I am so grateful the European Solidarity Center highlighted the significant role of religion in the Solidarność movement and Polish society in general.

Pingback: Women of Solidarność – Patrick C. Leech