Last week I wrote about the role of religion in the Solidarność movement, while I would not normally write about the same experience twice, there was another facet of my visit to the European Solidarity Centre that I need to tell. -PCL

As a historian, I am rarely surprised by the critical role women play in historical events. Yet, the erasure of women continually shocks me. This is one reason I enjoyed the European Solidarity Centre is it clearly describes the significant contributions of people who often are omitted from the story. If you are familiar with the history of Solidarity in Poland, you most likely know it was the first independent labor union in Soviet bloc and it was led by Lech Wałęsa. If you know a bit more, you likely know Solidarność started as a labor strike in Gdańsk that spread and gained widespread popular support throughout Poland. Sadly, even as a historian loosely familiar with the region and the period, I knew these bits and that Solidarność went underground during marital law and that leaders like Wałęsa were arrested but returned to prominence after martial law ended.

This broad narrative is not wrong, just woefully incomplete. For instance, why did the strike begin? Why did the majority of the Polish populace join the strikers? The short answer is because of women. On 7 August 1980, Anna Walentynowicz was five months from retirement when she was fired from her position at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk for her participation in an illegal labor union. Despite an exemplary career at the shipyard—where she gained some of the highest recognitions available to workers—Walentynowicz grew disillusioned with the Communist system which led to her transformation into a dissident. A week later, 14 August, workers at the shipyard went on strike in protest of Walentynowicz’s firing. She was one of the strike leaders who formed the Interfactory Strike Committee, alongside Wałęsa and other, which coordinated the striker actions of workers across the port. She actively participated in the strike, the formation of the Gdańsk Agreement, the formation of Solidarność, and Polish politics until her tragic death in 2010 when she and other Polish leaders, including the then president and senior military officers, died in an airplane crash near Smolensk, Russia.

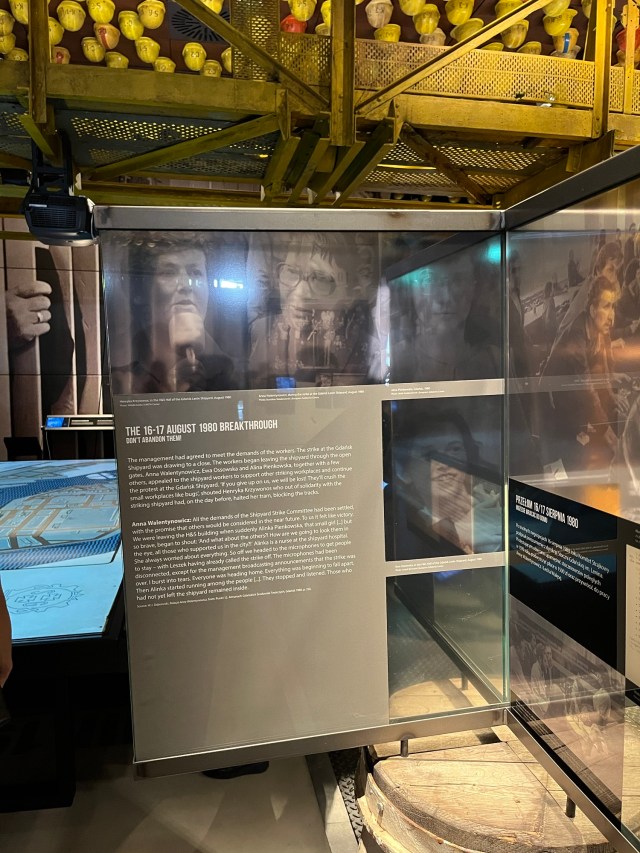

Alongside Walentynowicz, Alina Pienkowska was another leader of the Interfactory Strike Committee. Pienkowska worked at the shipyards as a nurse, and like Walentynowicz and Wałęsa participated in the illegal dissident/workers movement. During the strike, communication lines between the shipyard and the rest of the world were effectively cut, yet this did not apply to the clinic where Pienkowska worked. As such, she was critical to communicating to labor leaders around the country which helped the strike spread around the country. These sympathetic strikes pressured the government to accede to the 21 Demands of the shipyard workers on 16 August. Wałęsa and other leaders called an end to the strike, yet Pienkowska disagreed recognizing the critical role of striking workers outside of the shipyard and the vulnerability they were now in. The European Solidarity Centre exhibits included an interview with Walentynowicz who recalled how Pienkowska grabbed a bullhorn to rally the workers to continue the strike. She and Walentynowicz managed to close the gates and most of the workers agreed to extend the strike. Her actions resulted in all parties returning to the negotiating table which resulted in the Gdańsk Agreement and the transformation of the dissident labor movement into Solidarność. Later, Pienkowska secretly married another strike leader, Bogdan Borusewicz, continued working as a nurse, and served in elected offices prior to her death in 2002.

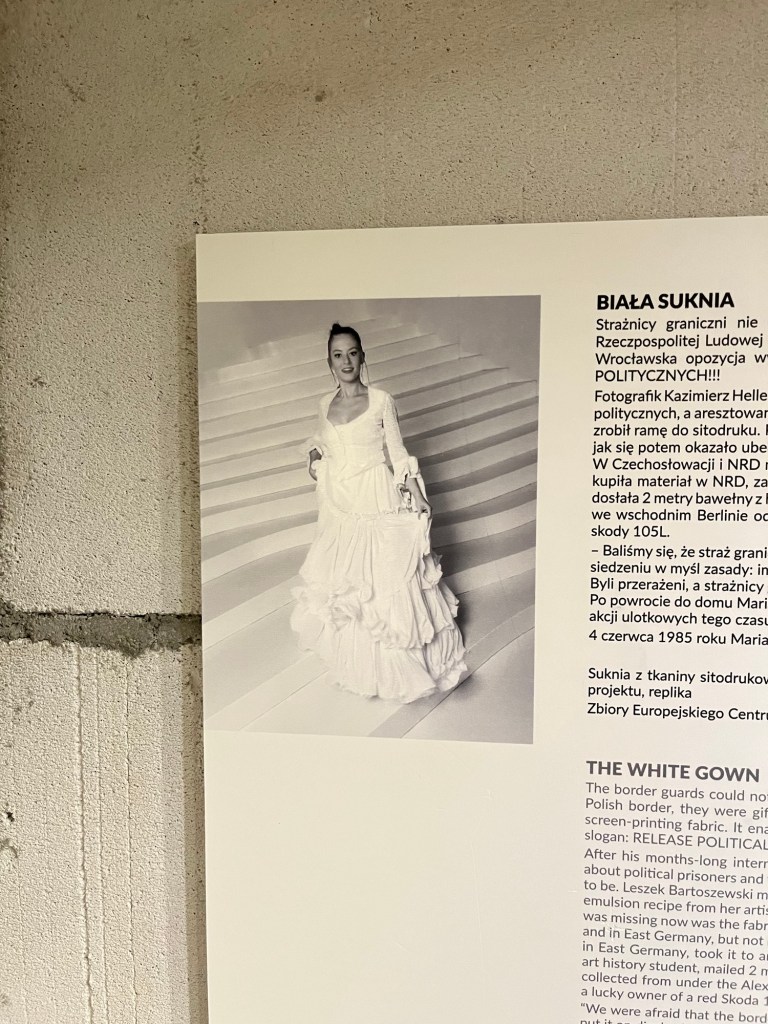

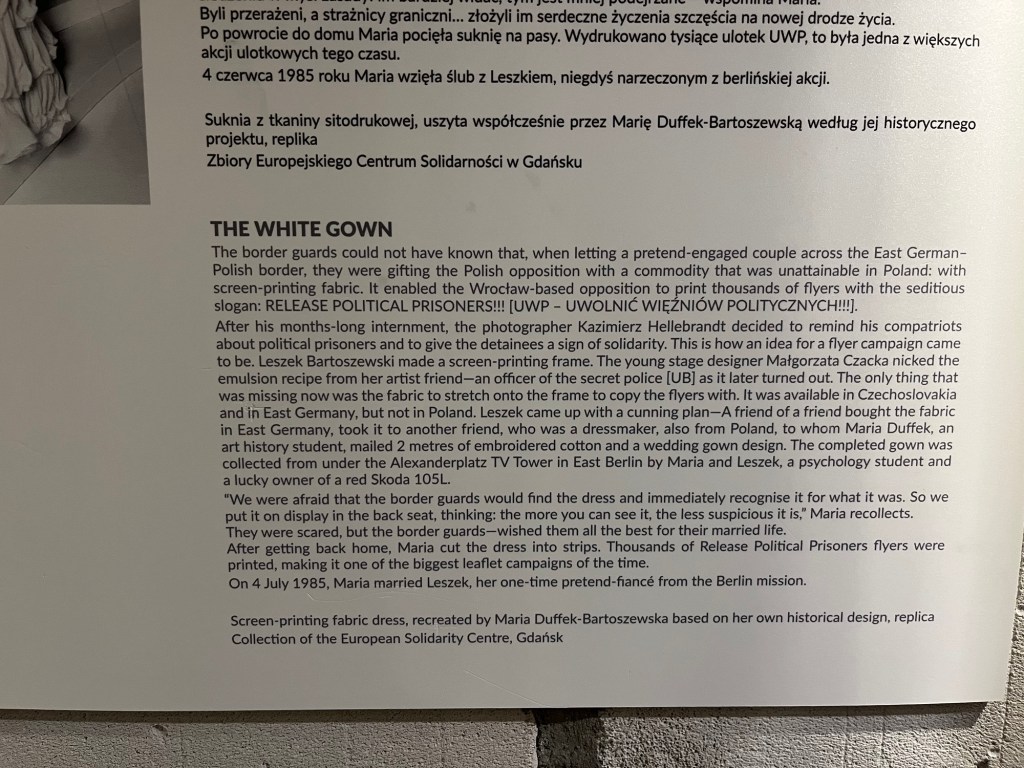

Leaders like Pienkowska and Walentynowicz are prominent, and their stories answer critical questions about the story of Solidarność making their participation easier to capture. Other stories are often more difficult to tell though no less important. For instance, in the middle of an exhibit about underground printing under martial law, stands an incongruous, white wedding dress. [image] The descriptive text explains this is a reproduction which make sense after reading the daring story of this dress. In need of printing materials, a group of students concocted an elaborate scheme to import clothe. Maria Duffek shipped some embroidered cloth and a pattern to a sympathetic dressmaker in East Germany. Then Duffek and Leszek Bartoszewski drove to East Berlin to retrieve the dress. Anticipating difficulty returning to Poland, the pair pretended to be engaged and proudly displayed the gown prior to crossing the border. The ruse worked and the border guards wished them a happy life together. The dress was dissembled, and the cloth used to tell the plight of the imprisoned political prisoners. Ironically, Duffek and Bartoszewski did eventually begin a romantic relationship and married. The exhibit includes a photo of Duffek in the dress alongside the replica she recreated. Duffek was not a labor leader but an art history student who eventually made a career in the Polish film industry.

Part of what made the exhibits at the European Solidarity Centre stand out is that these women were integrated into the story throughout the exhibits, because they were critical to it. While that may seem obvious, in many museums and history books women remain on the margin of the narrative regardless of their role. The beauty of the history of Solidarność is that it reminds us that the question is not “did women participate” but rather “what role did women play.” In fact, taking women out of the story not only changes it but what remains does not make sense. That is true not only for Solidarność, it is true for all of history.