One of the things I love about historical research is meeting people; sometimes that is at a conference or in the archive. And being a historian, sometimes those people are no longer living. No, historical research is not necromancy, rather history is similar to how G.K. Chesterton described tradition – it invites those from the past to participate in the present. Toward that end, I want to introduce some of the people from the past I met while writing my dissertation. These individuals often lived quiet, normal lives that would otherwise have gone unnoticed which is precisely why I want to highlight their actions. History is not just made by the great or powerful, rather it is built from the myriad contributions of individuals doing both the ordinary and extraordinary.

Succinctly, my dissertation traced the actions of Hungarian Americans, primarily in central New Jersey, as they responded to the arrival of Hungarian refugees in 1956-1957.[1] These diasporic Hungarians proved a vital component of the resettlement program by helping refugees navigate the procedural and cultural aspects of resettlement and life in the US. I focused on central New Jersey for two reasons. The first reason is the temporary facility for housing and processing the refugees was Camp Joyce Kilmer, then just outside of New Brunswick, New Jersey. The second reason is that New Brunswick and central New Jersey is home to a large Hungarian American community.

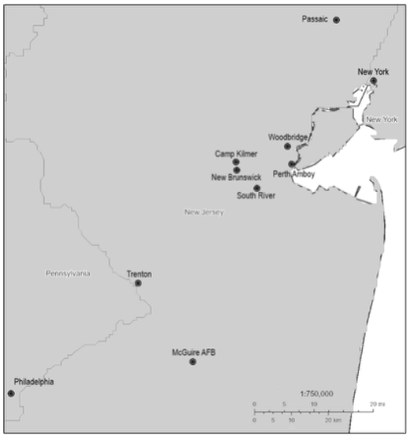

As such, geography is critical to this story. The selection of Camp Kilmer as the central reception area for Hungarian refugees came from its location and availability. The army originally built Camp Joyce Kilmer in 1942 due to its proximity to existing rail lines and the Port of New York City and it became a major point of embarkation for units transiting to and from the Europe Theatre during World War II.[2] When the Eisenhower Administration launched its effort to provide relief to Hungarian refugees in Austria, the mothballed facility was selected due to its availability and favorable location. That Camp Kilmer was adjacent to New Brunswick, New Jersey, was incidental, as was its proximity to the Hungarian diaspora.[3]

The local Hungarian American community proved an unexpected and equally critical resource. The heart of the Hungarian diaspora in New Jersey, New Brunswick is twenty miles southwest of New York City and the Port of New York, thirty miles north of Maguire Air Force Base, and thirty miles northeast of Trenton. The US Census 1940, enumerated 9,654 Hungarian-born persons in New Brunswick and Middlesex County, making it home to 28.5% of New Jersey’s Hungarian-born population at that time. This does not include second generation and other US-born members of the Hungarian American community which are difficult to track in US Census data. Nor does it include the postwar DPs. Today, the Hungarian community in New Brunswick remains vibrant with the American Hungarian Foundation maintaining a museum, archive, and community center which hosts an annual Hungarian festival each June. Additionally, Rutgers University houses the Hungarian studies program that August J. Molnar brought from Elmhurst College in 1956.[4] Additionally, the area supported multiple Hungarian-language newspapers which proved to be rich sources for my research.[5]

Thus, Camp Kilmer was not only close to major transportation infrastructure, but also in the center of a large, vibrant, Hungarian American community. While that community was not as populous as those in neighboring New York City or Philadelphia, this is largely a consequence of it being dispersed across multiple smaller communities in central New Jersey rather than concentrated in a single city. However, the largest contingent of the Hungarian diaspora in New Jersey was in New Brunswick and next door to Camp Kilmer. While the US government may not have considered this reality when reopening Camp Kilmer, the local Hungarians did and began to mobilize to assist the newly arriving Hungarians.

One of the most unique contributions from the local Hungarians was translation, an unsurprisingly critical facet of the resettlement program. With a small number of total speakers, Hungarian is not a widely spoken language and few people without direct connection to Hungarian culture learn the language and, few Hungarians, at that time, learned English. We see this is several ways, for instance Hungarian-English dictionaries and handbooks were in high demand by Camp Kilmer staff and the refugees themselves.[6] Similarly, diaspora newspapers contained numerous announcements seeking translators and Hungarian-speaking staff with one such announcement noting the need for Hungarian-speaking nurses to work in the hospital in addition to the desire to hire fifty translators capable of typing in English, and forty other translators with federal civil service benefits.[7]

This meant that not only were translators important they were also uncommon; thus, the bilingual members of the Hungarian American community were invaluable to the various operations in Camp Kilmer.[8] In addition to employed translators, dozens of Hungarian Americans volunteered as translators. One such volunteer translator was Melba Lórik from nearby Highland Park. As an American Red Cross volunteer, she donated over four hundred hours of her time to working with the refugees in Camp Kilmer. Her substantial volunteer hours then led to her selection as the translator for a group of Hungarian refugees who presented about their experiences at the 1957 national Red Cross convention.[9]

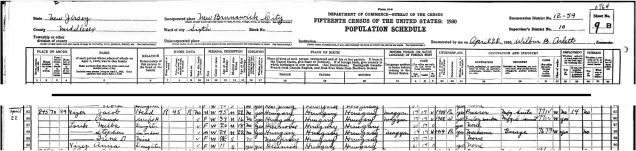

Lórik, was born in 1910 to Hungarian immigrants who arrived two years prior. In 1928, she married Stephen Lórik, who had immigrated from Hungary with his parents in 1914. The US Census 1930 indicates that Stephen, Melba, and their infant daughter, Irene, lived with her parents, Jacob and Anna, and that while everyone in the house spoke English, Magyar was listed as the “language spoken in home before coming to the United States” for Stephen and for Melba’s parents.[10] Since Lórik was born soon after her parents arrival in the US, it is reasonable to assume she grew up bilingual.

Lórik was one of over a thousand Red Cross volunteers from across thirty of the New Jersey chapters who worked in various capacities within the hospital at Camp Kilmer.[11] Similarly, Lórik also represents the hundreds of volunteers across the country described simply as “interpreter” or “Hungarian speaking.” These words obscure the fact that these people were part of the Hungarian diaspora and its response to the crisis. These hundreds of volunteers also stand as a reminder that historical events are made through the actions of local people working in their community. We live in a moment in which everything seems a national issue and our own actions are ineffectual or insignificant. Melba Lórik is a reminder that working locally not only has a local effect, but it can also reach much further as well.

[1] As a recap, in October-November 1956, Hungary experienced a large-scale revolt which toppled the existing government but triggered a military response from the Soviet Union to keep Hungary within the Soviet sphere of influence. One facet of that crisis was the flight of approximately 200,000 Hungarians from their homeland into Austria and what was then Yugoslavia. The US government ran an ad-hoc emergency program from late-1956 until the end of 1957 that resettled over 32,000 Hungarians into the US as part of its Cold War effort in Europe.

[2] Camp Kilmer was a temporary Army facility that opened in early 1942 as a transit post to facilitate the transfer of units, materials, and replacements in support of US involvement in the war in Europe. Once the war ended, Camp Kilmer functioned as an important site for men and units demobilizing from the European Theatre. After World War II, Camp Kilmer was decommissioned but reactivated in 1950 to support the US involvement in Korea. After the US draw-down from Korea, Kilmer was again decommissioned in 1955. During the Hungarian Crisis, over three thousand individuals from twenty-two military, governmental, and voluntary agencies contributed to the resettlement of over 36,000 refugees. In 1963, the Defense Department sold most of the 1600-acre facility to area universities. The final twenty-four-acre campus, the Sgt. Joyce Kilmer Army Reserve Center, closed in 2009. “KRC Manual,” sec. C–3; Alyn-Michael Macleod, “Historic WWII-Era Camp Shutters Doors,” Army.Mil, October 14, 2009; National Archives at New York City, “Exhibit: Camp Kilmer,” National Archives and Records Administration, April 9, 2018.

[3] Neither the White House statement, Voorhees’ papers and reflective essay, the operations manual, nor the Committee’s final report even acknowledge the presence or contributions of the local Hungarian population. Rather when discussing the location, they emphasized proximity to transportation networks. Special To The New York Times, “U.S. Sets Housing for Refugees”; “KRC Manual”; Presidential Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief, “Report to President,” May 14, 1957, Rutgers University Library, Tracy S. Voorhees Papers, President’s Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief, boxes K and L, folder Reports to President, Etc., 1957; Voorhees, “The Freedom Fighters-Hungarian Refugee Relief, 1956-1957 [Essay in Final Form].”

[4] Hungary, 1940. Social Explorer, (based on data from Digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited, and verified by Social Explorer.; accessed 26 November 2024 at 12:21:47 GMT-6).

[5] The American Hungarian Foundation Archive contains a sizeable collection of Hungarian-language newspapers which it digitized in participation with Hungaricana. Unfortunately, the collection does not include copies of Magyar Hirnök for 1956 but does include 1957. Laszlo Dienes, the editor of Függetlenség, also edited Magyar Hirnök and a review of the 1957 issues of both papers reveals significant overlap in their content and with his other papers. The shared ownership and high degree of reprinted material support accepting Függetlenség as a window into the New Brunswick Hungarian community.

[6] “FONTOS ÉRTESÍTÉS,” Jersey Hiradó (Trenton, NJ), March 7, 1957; “Advertisement, H. Roth & Sons Importers,” Jersey Hiradó(Trenton, NJ), May 2, 1957.

[7] Függetlenség, “A CAMP KILMER-ben még mindig keresnek alkalmazot takat, Függetlenség, Jan 10, 1957.”

[8] Jersey Hiradó, “NYOLC EZER DOLLÁR JÖTT BE EDDIG A KÖZÖS MAGYAR SEGÉLYRE, Jersey Hiradó, Nov 22, 1956.”

[9] “Magyar tolmács,” Függetlenség (Trenton, NJ), May 23, 1957.

[10] “New Jersey, Middlesex County, New Brunswick, Ward Six, Enumeration District 12-59, Sheet 9B,” Ancestry.com, 2002, 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

[11] “KRC Manual,” G-3 & G-4.