One of the most common complaints I have heard about historians is that they do not simply “tell what happened” they bring their own interpretations to the past. In some ways that is correct, yet it is rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding about the past. In prior posts I described the role of memory and myth in memorializing the past. So, this week, I want to provide a simple example of how a historian works with the past and why that is different than mythmaking while also something other than a chronicle of facts, but to do that I will draw on some examples that will likely be unfamiliar and seemingly unimportant. I ask that you stick with me as explaining the historical process and the philosophy of history is difficult. If these events are of importance with you, I ask your tolerance if my description overlooks important nuances, I hope you will find I omitted examples rather than missed important themes. Afterall, my intent is not to offend or disparage but to explain complicated events to an audience of non-specialists.

- In 1904, the Hungarian Parliament Building was completed. In its Central Hall now displays the Szent Korona (Holy Crown) which is surrounded by statues of sixteen Hungarian rulers including the Arpad Dynasty, Louis the Great, the Hunyadi kings, four Transylvanian princes, and three Habsburg monarchs.

- An armistice, or ceasefire, between Austria-Hungary and the Entente Power went into effect on November 4, 1918. A similar armistice with Germany, the sole remaining belligerent, seven days later.

- On December 1, 1918, the Great National Assembly of Alba Iulia declared the union of Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania.

- On March 21, 1919, Hungarian Bolsheviks proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The republic collapsed when its leadership fled the country on August 1, 1919.

- In August 1919, the US General Harry Hill Bandholtz arrived in Hungary as part of the Military Mission to Hungary of Inter-Allied Supreme Command.

These facts represent a portion of the knowable past[1]. What a historian does is select portions from that past to tell a story. For example, I could use these same facts to recount my recent tour of the Hungarian Parliament Building and Szabadság tér. I could also use these facts to explain why the end of World War I scarred the Hungarian people, in an essay about the development of the modern state of Romania, or a biography about one of the most celebrated Americans in Hungary whom few in the US have ever heard of. Instead, by blending these different stories I can explain why the production of history is a complicated and sometimes fraught process that is more than simply “telling what happened” or “describing the past.”

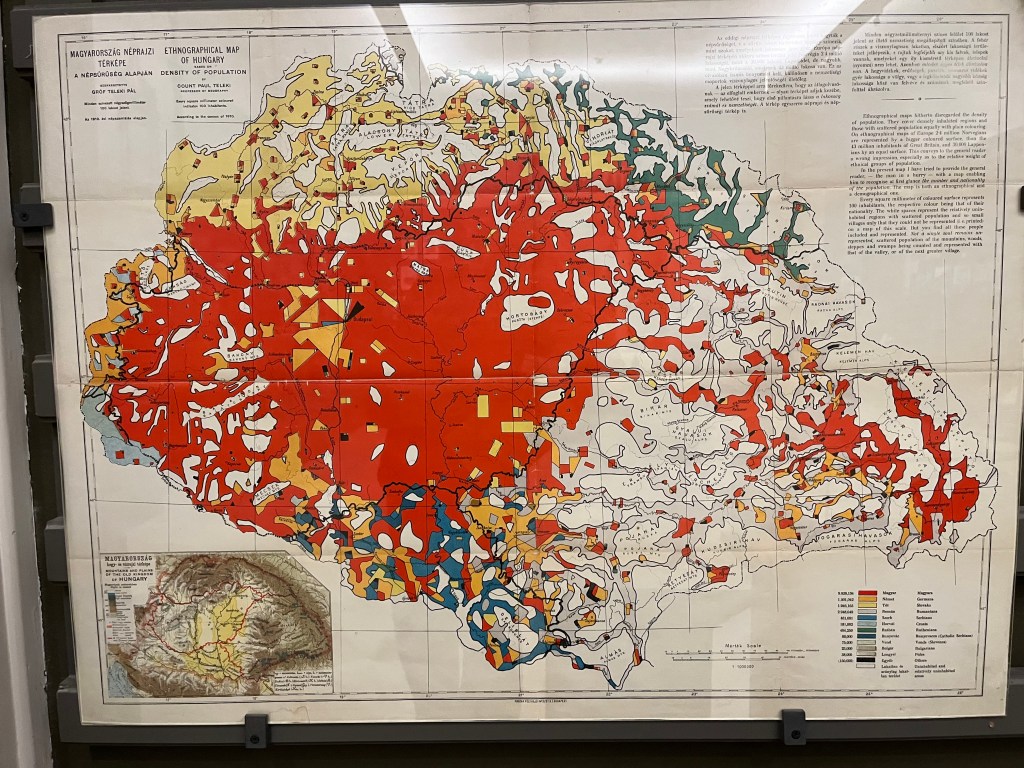

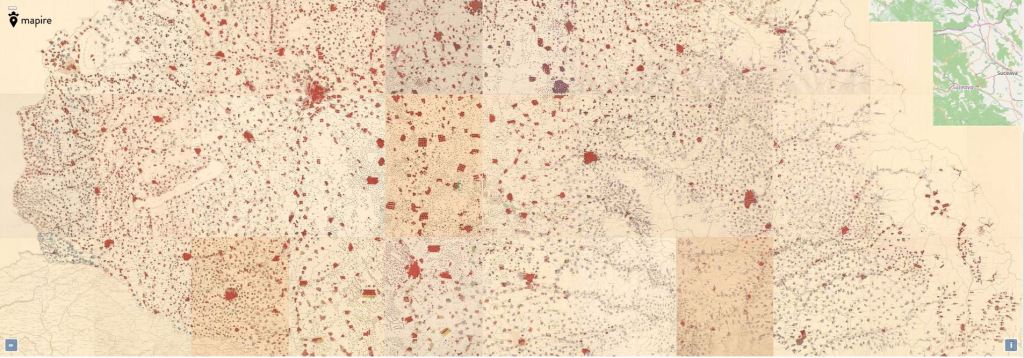

The arrival of a Magyar-led coalition of horse-mounted steppe peoples in the Carpathian basin in the late 9thCentury was one of several massive disruptions to early Medieval Europe including the division of the short-lived Carolingian realm and the arrival of boat-borne Scandinavian peoples we now know as Vikings. The Magyar were a small, heterogenous people whose spread across the vast spaces of Carpathian basin resulted in a sparsely population region with a Magyar Turkic governing class scattered among Magyar, Turkic, Germanic, and Slavic peoples. The heavily wooded southern portion of the basin became known as Transylvania, yet it is in this location that our story begins. While this region bears clear markers of previous Roman settlement, any connections between it and either Rome or Constantinople were gone prior the arrival of the Magyar. Nevertheless, starting in the mid-nineteenth century, Romanian nationalists, and later Romanian historians, state that the people of the region were the descendants of the Roman colony of Dacia. These Romanians generally agree that the Hungarians governed the region for most of a millennium, yet they assert the majority of the populace were of Roman descendent and thus possessed a stronger claim to the region due to population and longevity.

Historians would typically seek to resolve such competing claims through evidence, but this is one of the examples of the limitations of the knowable past. No one has found any evidence of census records or tax rolls from this period. And even if they did, any designations of identity would likely be hyperlocal and far from anything like a 19th Century idea of national identity. Archeologists help with evidence of peoples in the area, but they cannot answer how a group of people viewed themselves. Linguists can trace the origins of the names for the region back a thousand years, but that is still after the arrival of the Magyar, so it is not surprising that many believe the antecedents for the Hungarian term, erdély (beyond the forest), likely influenced the Latin term, ultra/trans sylvania, and the Romanian ardeal. In short, we do not have enough evidence to know, so instead we simply have competing myths—the stories a people tell itself about itself—rooted partially in the knowable past and partly within a political agenda.

While Romanian or Hungarian readers are potentially incensed, others are wondering the relevance of an unresolvable 19th Century dispute about the 9th Century to World War I. The short answer is that with Hungary on the losing side of the war and Romania allied with the victors, Romanian nationalists saw the opportunity to rectify a millennium of injustice. Simplifying a complicated narrative, in 1916 Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente with promises of gaining parts of the Kingdom of Hungary yet by May 1918, after the Central Powers have occupied the majority of Romania a separate peace is brokered that effectively returns to the prewar borders. Then on November 10, Romania again declared war on the Central Powers, in hopes of blunting harsh criticism from its former allies who will be responsible for the division of formerly Austrian and Hungarian lands. In response to US President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points which included statements about the right of national self-determination, various ethnic groups within the Habsburg domains began convening representative bodies and issuing declarations. The Romanian state used these declarations and its renewed status as a belligerent to slowly expand into pre-war Hungarian territory reaching Kolozsvár (now Cluj) located on the present-day Hungarian-Romanian border on December 24, 1918.

Meanwhile in Hungary, in late October 1918, the first Hungarian republic is formed, partially in response to President Wilson’s demands to negotiate with representative governments. That government reached an armistice with the Entente power on November 4, 1918. Disagreements between Internal factions, including on how to respond to Romanian incursions prevent the creation of a stable governing coalition, and on March 21, 1919, the Bolsheviks ceased power and declared their intent to regain the occupied territories. While rebuffing Romanian claims for nearly half of pre-war Hungary, the Entente Powers/Paris Peace Conference feared the spread of Communism and therefore tolerated the Romanian invasion of Hungary which resulted in the occupation of Budapest on August 6, 1919, just days after the Bolshevik government fled. During this time, the peace conference sent a military mission to Hungary, which included General Bandholtz, to facilitate the reestablishment of a responsible Hungarian government and to resolve conflicting claims of interethnic violence between the Hungarians and the Romanians. According to Bandholtz, shortly after arriving in Hungary he thwarted Romanian attempts to arrest the newly selected Hungarian Prime Minister as well as their attempt to loot portions of Hungarian heavy industry.

By now, Romania occupied most of Hungary, including all of Transylvania, and claimed full control and union with the latter region. With these claims, Romania also appears to have claimed the rights to all artefacts from the region housed in Hungarian National Museum. Both the museum and Bandholtz credit him with single-handedly preventing the Romanians from entering the museum with a riding crop and dubious orders. In honor of his efforts, the Hungarian erected a statue to Bandholtz outside the US Embassy, placed a plaque on the museum commemorate the events, and include a sizable exhibit about him in the museum itself. The US Army credits Bandholtz with the formation of the military police, yet otherwise he is virtually unknown in his homeland.

Yet, in a 1920 interview with the New York Times, Bandholtz described his actions at the museum as also preventing the theft of gold treasure by the Romanians. This claim sparked a diplomatic incident which resulted in the claim being retracted and an official note from the US State Department to the Romanian legation in Washington, D.C. Additionally, when the statue was installed in 1936, the Romanian government objected.

This returns us to the problem of creating history. In the previous post I described the problems of memory and its linkage into myth. The incident at the museum highlights how this plays out in the writing of history. Unlike in the 9th Century we have witnesses and evidence, yet because of their limited perspectives, biases, and other unreliability how do we know what happened. Bandholtz’s comment about gold treasure could be an attempt at self-aggrandizement or it could be a poorly formed description of the presence of various artefacts made of gold, including the Szent Korona which was then housed in the museum. The Hungarian adulation draws heavily upon anti-Romanian tropes that depict the latter as brutish, violent, philistines. Yet the Romanian version is part of a nationalist narrative that portrays the Hungarians as abusive, plundering, occupiers. As such, the memories and other evidence are shaped by the self-perceptions of the bearers and myths they held.

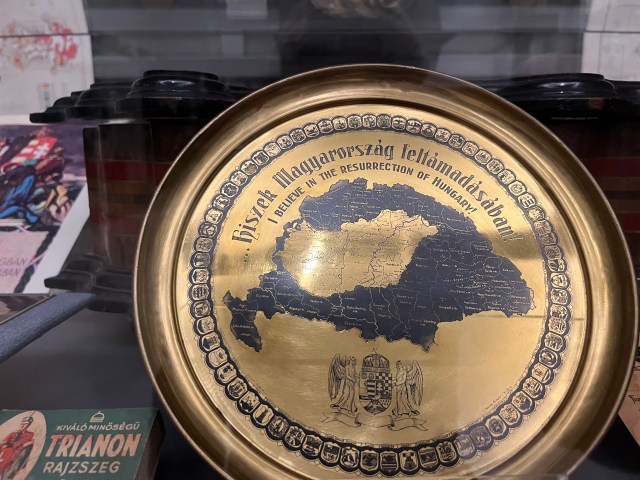

So, whose facts does a historian use to tell this story? In the Treaty of Trianon, the peacemakers compromised by granting Transylvania to Romania but rebuffing claims to further territory, yet in the process stranding around a million Hungarians despite promises of self-determination. This became an additional source of tension between the countries that persists into today. Thus, a compromise approach clearly is insufficient; yet telling these histories drawing from all the strands is not only complicated it is impossible to gather all the evidence together, and the result will still be unsatisfactory to most, if not all.

Instead, historians must select from the evidence available; weigh its biases, perspectives, omissions; and balance those with other evidence, while recognizing that essential information is missing. Then the historian must assemble that information and the analysis into a coherent narrative that they know is imperfect and will be subject to review by other experts in the field who will disagree with them. Additionally, that narrative may conflict with a national myth and draw negative attention from political leaders. Yet, one of the core components of history is not to simply accept widely held beliefs simply because they are popular. Rather, the historian is to interrogate the evidence, their own assumptions, and even the myths they may hold. That is what makes history different than myth, myths provide certainty while history is rooted in uncertainty.

Plate on display at the Hungarian National Museum.

As people we do not like uncertainty, particularly when it is offered in critique of the certainty we have long held. While comparatively few people care about the tensions between the Hungarians and Romanians, we all have our equivalent moments from a messy past that we would rather not be examined and might resist historical analysis. Yet, by considering this facet of the complicated past of Transylvania we can understand the difference between the past, memory, myth, and history that can be applied to other areas of intercommunal conflict like India and Pakistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia, Israel and Palestine, or White and Black in the United States.

[1] In lieu of a long essay about the philosophy of history, the knowable past is the portion of human existence that is available to scholars. This cannot be the complete past because parts of human existence have been lost, destroyed, or never recorded. So, the knowable past is shorthand for the limited materials a historian could draw upon for a topic and will vary based upon the time period, the location, language, and media (papers, stone tablets, art, oral traditions, etc.).

Beautiful facts about the past. The battle of ideas with Hungary are still alive in Romania!

LikeLike